No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Working in a restaurant kitchen is notoriously stressful. A daily routine filled with precise techniques, an ever-ticking clock, and the constant pressure of hundreds or thousands of people critiquing your work, needless to say, those that thrive in these conditions have a high-stress tolerance. However, that doesn’t mean BOH employees aren’t susceptible to the detrimental impacts of being stressed out at least 10 hours a day, so here are some skills and tricks to help manage the pressures of the kitchen.

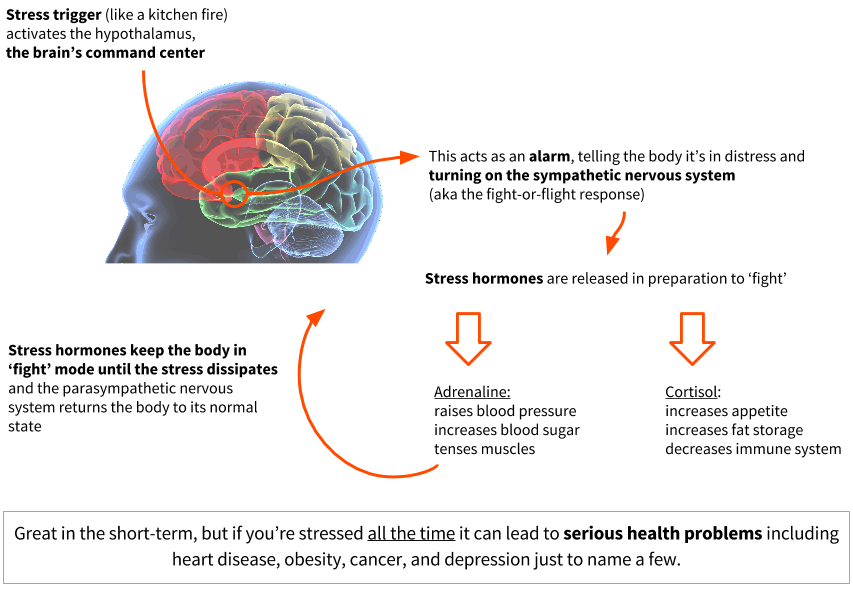

Before getting to management, to understand the importance of it, it’s best to understand how our bodies deal with stress. Check out the infographic below.

As shown above, if you’re chronically stressed, there can be some major consequences. This is why it’s so important to find constructive solutions to manage the intense pressure that comes with working in the back of house, so here goes.

Working in the industry means having good, bad, and downright bloody ugly days. We’ve all experienced a shift after which we simply wanted to go home, crawl under a rock, and never come out. This is why everyone, especially those that work in restaurant kitchens, should have a way to unwind outside of work.

If you’re thinking that you do and it’s with alcohol, think again. Although alcohol may help us unwind in the moment, it actually keeps our bodies’ stress response in full swing. In fact, studies have found that alcohol increases the release of cortisol to levels higher than that of a true stress response. While a drink or two after a shift is perfectly fine, and even shown to be healthy in some cases, more than that will do you more harm than good.

Instead, try doing something that takes your mind off of work but keeps it engaged like an outdoor activity, watching movies, karaoke, video games, enjoying good conversation, reading, working in the yard, chess, working out, or anything else which you enjoy doing. The possibilities are endless.

The typical plan of action usually covers what needs to be done on a normal day…here’s my menu, here’s my prep list, and this is who’s responsible for each station. However, as I’m sure you know first hand, even the best-laid plans fail (hello Murphy’s Law).

That’s why it’s never enough to make a plan solely based on what you need to accomplish. Your next step should always be to evaluate how that bastard Murphy could show his face and screw everything up.This is where always having a “plan B” just in case is the best plan of all.

Your plan B should provide a solution for things such as equipment failures, guests arriving late/early, being short-staffed, and covering for others just to name a few.

This will not only ensure that you keep your head in a crisis situation, but also keep your stress levels at bay.

Even knowing that if something were to go wrong, you’re prepared, will keep your anxiety low and stress in check. So, hope for the best, plan for the worst.

A common stress trigger is time, or lack thereof, so finding places to save even a few seconds can be a huge stress management tool. If you can shave five seconds off of the service time of every dish you’re prepping or cooking, you’ll be eliminating several minutes work throughout service.

Not only will the speed of service increase, but the stress level throughout the kitchen will decrease.

Whether you’re in a lead role or just starting out, take a few minutes to think of the workflow in the kitchen to see if there’s anywhere you can find these precious seconds. This can be from changes in prep to reorganizing the kitchen.

All of us have worked under poor upper-level management. Whether it’s that imbecile manager who sets unachievable budgets and then tears you up for not being able to meet them or it’s the lazy operator that takes all the credit for your hard work, it’s not worth putting up with it for long.

Endure them only as long as you have to because their arrogance and stupidity will not change, but your stress will only build.

The bottom line is, if you are unhappy in your current position because of those in authority over you then it’s time to move on. Put in your year (for resume history purposes), do your job to the best of your ability, don’t burn bridges, and get out.

Do not ignore problems… they rarely go away and usually only get bigger. Every position in the back of house has their own challenges based on their responsibilities and personalities. If you see a problem, deal with it immediately.

Decide what needs to be done, when you will do it, and what type of follow-up is required. Rip the bandaid off!

Whatever you do, don’t ignore the signs of chronic stress. If you’re not feeling or acting like yourself, take the time to find the right tools and techniques to manage your stress before it’s too late.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

The craft spirit industry is in the midst of a boom, but confusion remains about what exactly qualifies a spirit as ‘craft’ and, as a consumer, how to know if what you’re buying is actually considered ‘craft’.

What Is A Craft Spirit

Unlike craft beer, there is no national, over-arching legislation defining what can be called a ‘craft’ spirit. No production minimum, no control of additives or ‘fake’ ingredients (outside of existing parameters for specific spirit categories), no corporate vs. private ownership status requirement.

Adding to the confusion is that a ‘craft’ spirit can be made from a non-craft base.

In the case of craft vodkas and gins, the base spirit often originates from a neutral spirit purchased in bulk from industrial suppliers. As for whiskey, independent bottlers who purchase aged whiskey by the barrel then blend, or ‘cut’, it to create something new can also be considered ‘craft’.

As you can see, there’s a fair amount of gray when it comes to what is and is not a craft spirit. However, industry advocacy groups, including the American Craft Distillers Association (ACDA) and the American Distilling Institute (ADI), have created some guidelines to address the question, mostly based on ownership and production/sales numbers.

Production-wise, the general consensus is that to be considered ‘craft’, no more than 100,000 proof gallons can be produced per year.

For comparison’s sake, Bulleit, Hendrick’s Gin and Woodford Reserve each sells between 200,000 and 300,000 cases annually.

As for ownership, both groups maintain that in order to qualify as a craft spirit, the distilled spirits plant (DSP) where the spirit is produced must be independently-owned.

Meaning “less than 25% is owned or controlled by alcoholic beverage industry members who are not themselves craft distillers.”

ADI goes a step further in its qualification rules by not only including a provision about ‘vision‘, but by also distinguishing between ‘craft distilled’ and ‘craft-blended’ spirits, the former requiring that the spirit is distilled by the DSP itself while the ladder originates from a non-craft base.

How To Tell The Difference

So, let’s summarize. A craft spirit is one that is produced in smaller quantities by an independently-owned distillery, of which there are essentially two types:

CRAFT DISTILLED SPIRITS: Goes from grain to bottle in-house at the craft distillery; the bottle declares “distilled and bottled in..”

CRAFT-BLENDED SPIRITS: Originates from commercially produced spirits that are then blended by the craft distillery; the bottle declares only “bottled in…”

Although a bottle may make several references to a state, like Tincup does with Colorado, this does not mean it is a craft distilled spirit unless the label specifically reads “distilled and bottled in…” In Tincup’s case, it does not; Colorado refers to the fact that the whiskey is cut with local water, so it is a craft-blended spirit.

If you’re thinking this is quite deceiving, then you’re on the money.

The craft spirit industry is full of clever marketing meant to entice buyers. Words like “small batch” or “handcrafted” may look good, but, remember, the only way to truly know what you’re buying is by looking at the writing on the label!

The best bartenders get a kick out of knowing they’re helping people have a good time – but what if it goes too far? Should bartenders be to blame if someone drinks themselves into injury or illness?

Bartending is a profession dedicated to the art of hospitality, but working with alcohol is not a position of power that should ever be taken lightly.

While the cocktail sector is exploding with boundary-pushing innovation, it is imperative the industry does not become detached from the dangers associated with what is, after all, an intoxicating drug.

In numerous countries including the UK, the US and Australia, legislation has been put in place making it illegal to sell alcohol to a person who is obviously drunk, and similarly, to buy an alcoholic drink for someone you know to be drunk.

However, despite the foundation of such laws, questions abound over who is responsible for ensuring the industry is not plagued with a problem of over-consumption.

During recent months, the media has been awash with a string of high-profile tragedies involving the apparent “over-serving” of alcohol, a handful of which have had calamitous consequences.

In April 2015, Martell’s Tiki Bar in Point Pleasant Beach, Jersey Shore, US, was fined $500,000 and had its licence revoked for a month after allegedly over-serving alcohol to a woman who later died in a car crash.

The incident unfolded in 2013 after Ashley Chieco, 26, left Martell’s in another person’s car, which collided with an oncoming vehicle, killing herself and injuring the other driver, Dana Corrar.

The survivor suffered two broken legs, broken ribs and will “never work again, never walk again normally and never be pain-free,” according to her lawyer, Paul Edelstein, a personal injury specialist. Martell’s pleaded “no contest” to the charge of serving alcohol to an intoxicated person in exchange for the fine.

“Businesses that profit from the sale of alcohol are well aware of its dangers, particularly when combined with people who then get into vehicles.”

Edelstein adds that “it is akin to a shop selling bullets and then allowing its customers access to a gun when they leave. Hopefully, the attention alone will make a bartender think twice before continuing to serve someone and inquire as to how they are leaving a location that does not provide access to mass transit.”

So when it comes to alcohol consumption where does the responsibility of the bartender start and that of the consumer end?

For some, all persons involved – the consumer, bartender and management – have a collective duty for the wellbeing of both patrons and staff.

“It’s everyone’s job to make sure the guests are happy and safe at the same time,” comments Kate Gerwin, general manager of HSL Hospitality and winner of the Bols Around the World Bartending Championships 2014.

“First and foremost, obviously the customer should know their own limits, however we all know that is not always the case. Bartenders should make safe service of alcohol a huge priority in day-to-day business and the owner of the bar should take a vested interest in the education of the staff about over-serving and the dangers and consequences.”

But for others, the responsibility rests with those in a managerial position who need to step up to their line of duties.

“Inevitably, the responsibility lies with the management chain – they are the licensees,” says British bartender and entrepreneur JJ Goodman, co-founder of the London Cocktail Club.

“In the UK we have an inherent history of binge drinking, so customers aren’t very perceptive to being told they’re not allowed another drink. When that sort of situation occurs, someone more senior and experienced needs to come in to handle it and command control as quickly as possible.”

Similar snippets of advice surrounding this irrefutably sensitive subject are echoed throughout the industry.

Accusing guests of being drunk is deemed as the biggest faux pas, and a sure fire way to escalate an already testing episode.

Avoiding embarrassment, ascertaining a first name basis and gaining the aid and trust of any peers who may be present are all recommended methods when it comes to diffusing any drama involved with this task.

Various initiatives have been instigated to curtail irresponsible service and consumption. At the end of 2014, the British Beer and Pub Association launched a poster campaign in the UK to drive awareness among consumers and on-trade establishments of the law surrounding serving people who are obviously drunk.

“It’s not about getting more prosecutions; it’s about raising awareness.”

Brigid Simmonds, chief executive of the British Beer and Pub Association, continues by explaining that, “it’s important we don’t turn pubs and bars into fortresses – we want to encourage people to go to these socially responsible places. But we need to find a balance between staff responsibility and personal responsibility.”

This article originally appeared in The Spirits Business.

It’s not uncommon for there to be tensions between restaurants’ front and back of house staff. From opposing personality types to the contentious fact that only the FOH gets tipped, animosities can run high and ultimately cause the quality of service to suffer. However, it doesn’t have to. Although the BOH and FOH may never be besties, the two can work as a team so that service is at its best. Here are a few ways the BOH can help to make it so.

“The BOH needs to know the reality—a team effort between FOH and BOH determines the quality of service.”

Adam Weiner, Culinary Arts Instructor

When that happens, the servers will think the BOH staff are heroes.

FOH should only be present in the kitchens their jobs require. No more, no less.

The bottom line is that there needs to be an understanding between the front and back of house that personal differences come second to service, and that working as a team will only prove to help this cause.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

The food truck fad has had a significant impact on the food & beverage industry, creating a new approach to serving food and granting many the opportunity become small business owners. However, as popularity grows, food truck owners are starting to feel the pressure.

One of the main challenges encountered by food trucks nationwide is coming from backlash within the community.

With the harsh sentiment that pop-up businesses, such as food trucks, enjoy an unfair advantage and negatively impact trade, business owners with established reputations and a stake in the community are making their complaints heard.

The American Dream seems to be in question.

While city politicians like to stand behind that dream, they are also responsible for protecting local commerce, leading to ever-changing legislation, some of which helps food truck owners succeed and some of which dooms their business to failure. These regulatory changes are ongoing, from the Pacific to the Atlantic, potentially opening doors in Seattle while closing others in Texas.

For one former food truck vendor who plied his trade in the middle of the country, the continual changes proved to be too much. His 2014 experience that welcomed the new year with a mad rush of investment ended at Christmas with disaster and debt, a common story heard all across the country.

Eddie Lawrence, a former food truck owner, believed with every fiber of his being that Americans would rush to try his very British, unsalted version of fried Atlantic cod with a heaping pile of hand-cut fries.

His venue near the center of Bentonville, Arkansas seemed like a shoo-in. However, red flags flew early on when Bentonville’s mayor Bob McCaslin learned too late that Lawrence had received his business permit from City Planning. Summoned to City Hall, Lawrence tells us McCaslin was none too happy.

“He went on about how he wouldn’t have approved it and I wasn’t going to get renewed next year, neither.”

And sure enough, as the weeks progressed, the city dispensed regulatory updates that hindered business for Eddie and a half dozen other local vendors, a few of which were long-established in the close-knit community of businesses around Bentonville Square.

While legislative changes did make things more difficult, it may not have been the main cause of Eddie’s business failure, as well as that of almost every other Bentonville food truck.

Compared to local legislation, standard business regulations have a much greater impact on the entire concept of the pop-up business.

One problem Eddie remembers was an unexpected introduction into sales and employee taxation requirements. As new vendors came into the area, he found they were as much in the dark as he was, and made a point to give them a heads-up on the tax situation. In the end, he says his quarterly unemployment insurance

Beyond the government and the law, there seems to be another consistent factor causing these food trucks to end up out of business. Many of these small businesses are run by just a few who may not have much experience running a company.

In the end, the lack of know-how seems to be the nail in the coffin.

Currently, the cost of food trucks has plummeted as an increasing number of barely used trucks and trailers find their way into consignment lots. Eddie Lawrence was lucky, since he built out his own trailer. He reports a loss of about half of the build cost by the time he finally managed to sell it almost a year after closing, and counted himself lucky at that.